Who are they?

The Line is a BAFTA-nominated animation studio based in London, with a portfolio that boasts a wide variety of animation styles, primarily focusing on 2D animation. They started as a team of 6 animators working freelance, before growing into a fully functioning studio with clients and collaborations that range from Blizzard to Riot Games, and Chobani to Gorillaz. Their style is incredibly versatile, and they deliver consistent work of very high production quality, clearly reaching their goal of elevating everything they touch (The Line, 2024).

Exploring their work

They have an impressive portfolio that heavily favours 2D frame-by-frame animation, which is something I rarely see in studios these days. With 3D animation becoming more and more accessible and efficient, 2D frame-by-frame techniques have begun to take a backseat to its more efficient counterpart; vector-based 2D puppet animation. The Line still keeps strong with their commitment to traditional digital 2D techniques, and this is what drew my eye to their work in the first place.

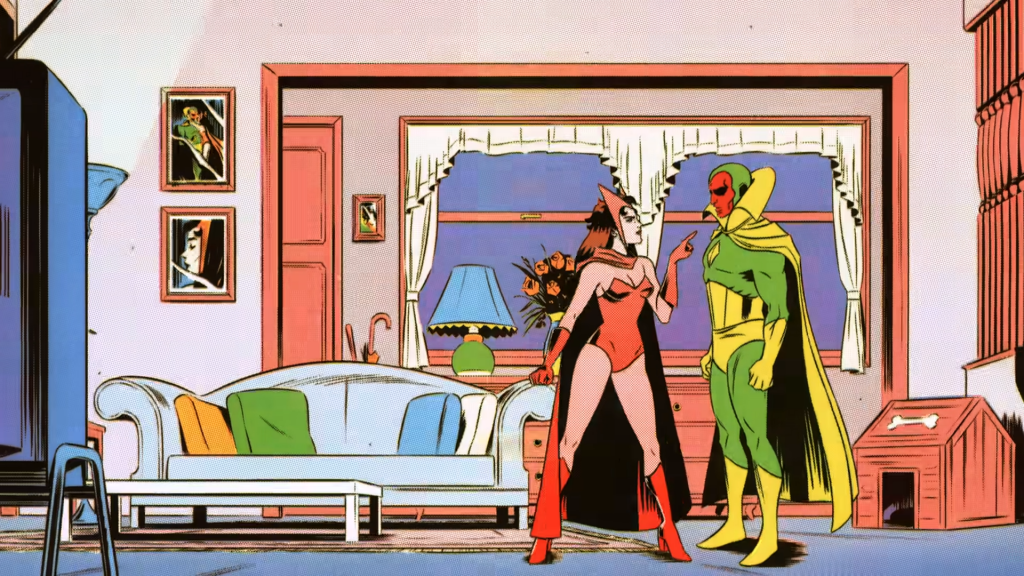

Their project for Chobani caught my attention way before I knew anything about the studio, but it was a more recent project for a Marvel game that prompted me to track down the studio. The music video transitions through multiple nostalgic comic book styles, with a narrative that is easy for those who aren’t fans to relate to, yet ties in well to the characters in the Marvel universe that feature in it.

From these stills, you can get an idea of how vibrantly different the visual styles are and the techniques that have been used. Image 2 is clearly inspired by early X-Men TV shows of the early 90s, while Image 3 features a risograph print style that is reminiscent of early halftone-printed comics. This scene was animated in 2D, and then each frame was printed and scanned to ensure an authentic effect. This kind of experimentation shows a deeper understanding and value for the material of the brief; they know their client’s story and know how to present it best.

This project, among other incredible productions in their reel, really warmed me up to the option of commercial work. Personally, I would prefer to attach myself to a studio that focuses on stories for film or TV, however, this type of work has its own attractive qualities. The wide array of styles and subject matter is appealing to me as I believe it will keep my attention, and also push me to be more versatile in my style and creative approach. While work for clients is generally thought to be more stifling and has its restraints, seeing what The Line can do with these parameters is greatly inspiring.