Context

As I approach the final month of the MA Character Animation program, the reality of transitioning from student to professional is both exciting and imposing. After two years of intensive study, countless late nights perfecting walk cycles, and pushing the boundaries of character performance, I’m now faced with the challenge of applying all that learning into a compelling professional presence.

Website

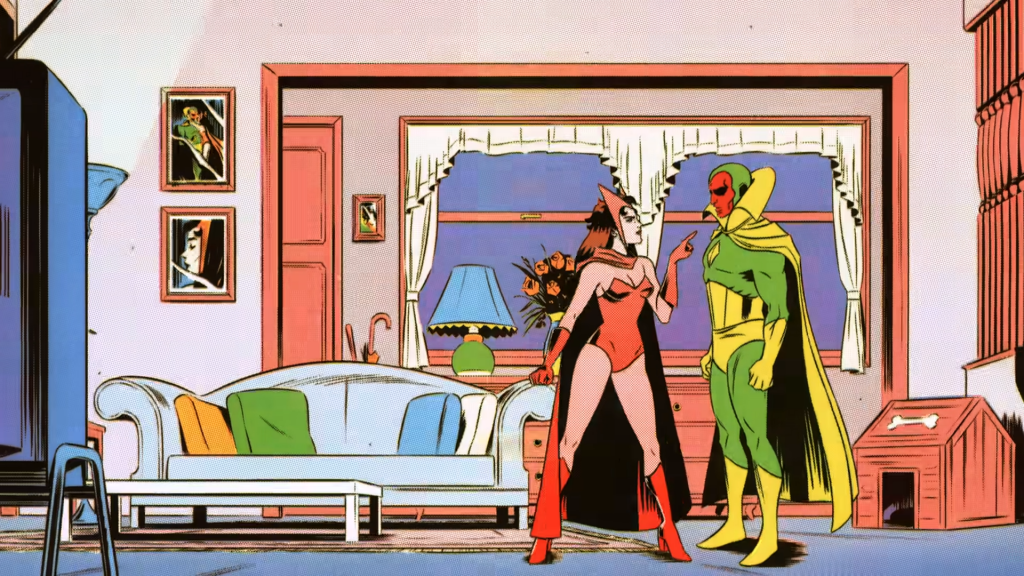

The first major task I’ve tackled is building my portfolio website. This has proven to be almost as creative a challenge as the animation work itself. I want potential employers to experience my work in the best possible light, while also displaying it in a way that expresses who I am as an artist. The site is a careful curation of pieces that showcase my range and technical skills, or at least I hope so. My hero piece – the graduation film we are submitting this week – will take centre stage, but for now it will feature my LIAF film, other assignments, and personal projects. The website needs to load quickly and look professional across all devices, so I’m still tinkering with making it accessible and efficient. I have barely worked on the mobile version, so it does look pretty rudimentary on that front.

Another major learning curve for this has been ensuring a good user experience while on the site. As much as I had my own lofty goals for creating a “cool” site, I soon learned that navigation and clarity were far more important, especially when considering the site’s primary purpose is to be shared with potential employers. After sending my first version of the site to friends to test and use, I returned to it with better insight on how to make the pages more accessible and the overall user experience more intuitive and friendly. Below is a quick video of the layout as it is in its current state, and here is a link to the site itself.

Showreel

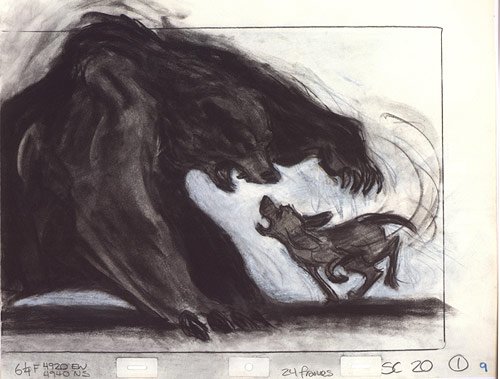

We had some great speakers in class talking about their showreels and how they approach reels as employers as well. In my research into the topic, I found a few videos and sites with more helpful information. Looking at other creatives’ reels also helped me understand the quality of work that is out there.

Here’s a link to the reel I created (as it’s too large to upload here). It’s got a long way to go, as it could be trimmed down much more and edited with a discerning eye. I look forward to the showreel event we will have at uni, as it will provide me with more critiques which will no doubt make the reel much better.